Home// Articles// Fundraising// How To: Raise a Series A

How To: Raise a Series A

Russ Wilcox

CEO at Trellis Air

Russ Wilcox

CEO at Trellis Air

Introduction

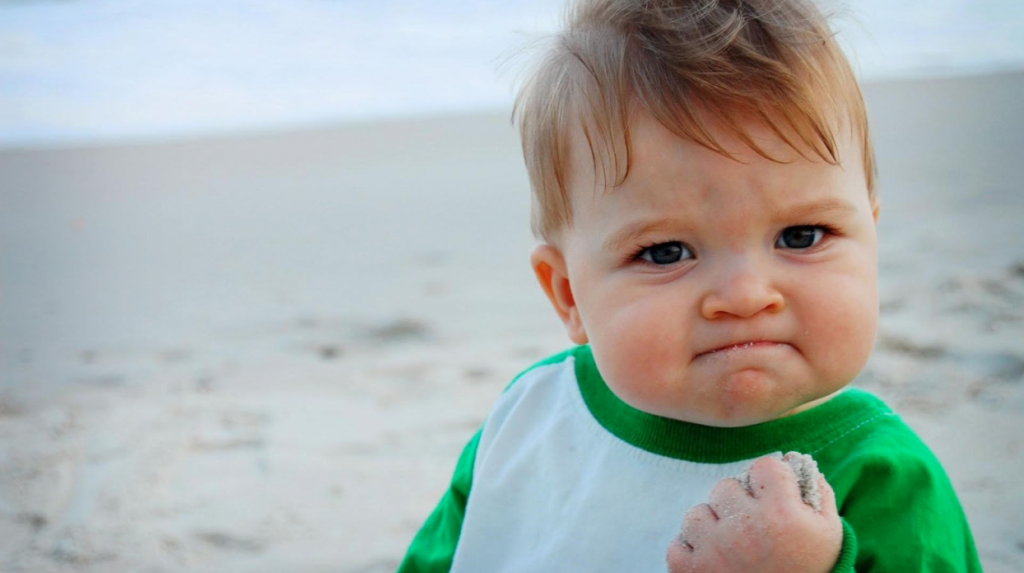

Congrats! You've just closed your Seed round and your business is on its way.

Take a moment to pat yourself on the back. Out of the 600,000 companies started in the United States every year, only 1% raise seed capital from angels, and only 0.5% raise seed capital from institutional VCs.

Raising seed was a grueling process, and you feel eager now to leave behind all thoughts of funding and finally get back to building your business. Perhaps you have your eyes on a well-earned vacation as well?

Definitely take that vacation and rest up, because while getting this far is distinctive, you are by no means assured of success in the months to come. Only 25% of venture-backed Seed deals successfully raise Series A immediately after Seed. Another 25% first require a Seed Extension, and then figure out how to make an adjustment, and that enables them to raise Series A.

The bottom 50% of Seed deals do not survive to raise Series A.

Why? Mostly because innovation is so hard! That’s why Hollywood producers would rather back a sequel than take a chance on a new story, and why talking with customers early (to confirm the idea is worth building) is so vital. Other common pitfalls: founder squabbling, engineering delays. Unless you overcome all these Seed execution challenges, there will be no point to raising Series A.

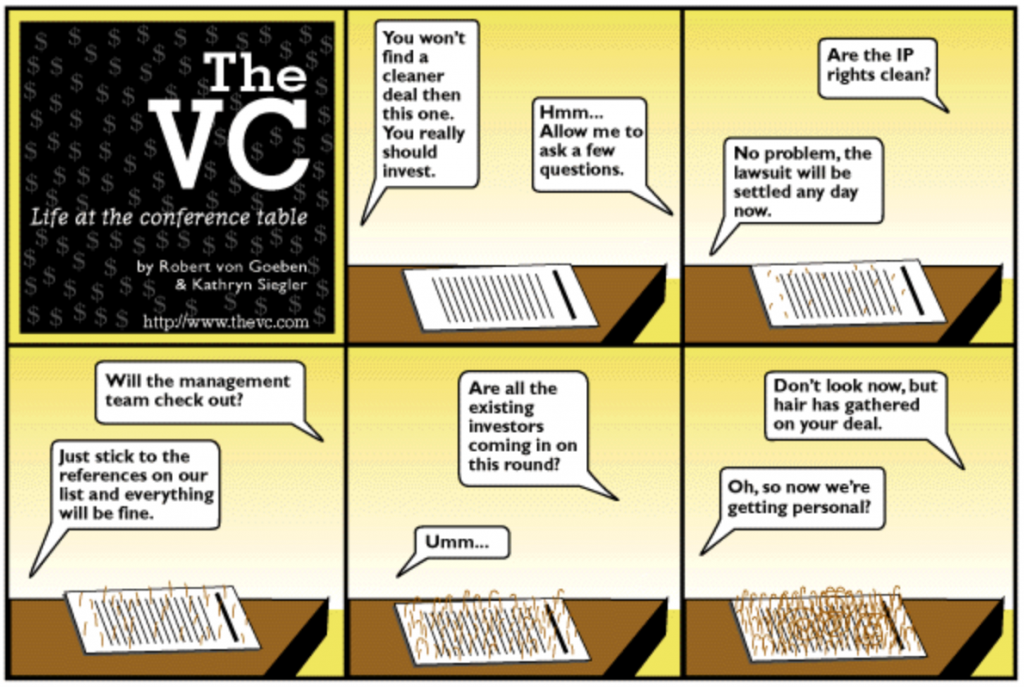

Once you have built a company that justifies further capital, you will be ready to start raising Series A – a multi-month process where you try to convince jaded professional investors to trade you $10-15 million of cash for a one-page stock certificate. No easy task!

How can you beat the odds and raise your Series A?

Read this guide, and apply its lessons.

1: Define Your Hurdle Raising Series A

Soon after you close your Seed round, plan ahead for the Series A. Start by identifying the 2 or 3 metrics that determine whether you are ready for Series A.

What do we mean by Series A? Here is our breakdown of rounds and roles:

In short, if you have product-market fit, you are raising an A round.

If you do not have product-market fit, you are raising a Seed or Seed Extension.

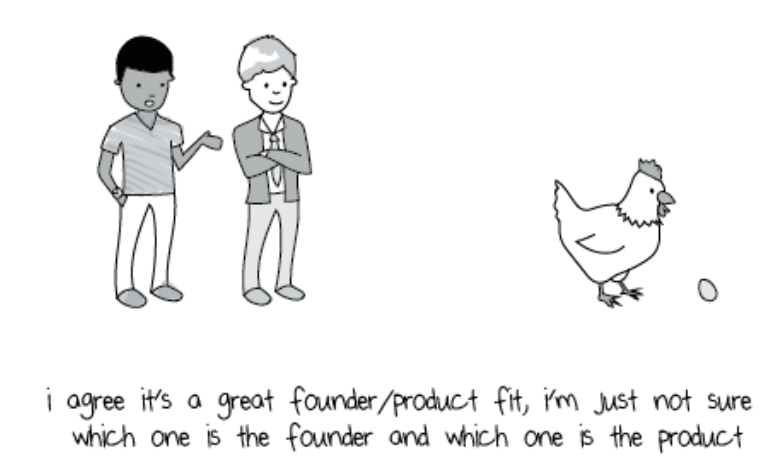

Art Papas defined product-market fit well at a recent Pillar workshop. Art is the Founder and CEO of Bullhorn, the leading software for staffing agencies which he has grown to over $200 million in sales and 700 employees. He’s built both successful and failed products.

Here’s his litmus test:

Proof of Product-Market Fit

- Customers have a clear and burning need.

- They are willing to pay a price that is meaningful to them.

- After you deliver the product, customers are “raving and renewing.” They actively buy more and they tell others.

- Customers are demanding more features from you and are willing to wait or even fund you to develop.

You will know you are ready for Series A financing if the opportunity has unicorn potential and you can see revenue is starting to take off because customers are spreading the word about a product they love.

How to turn that into metrics so you can track progress and keep yourself honest?

If you are a SaaS company, there are several commonly discussed metrics. VCs say that a company is ready for Series A if it can achieve annual recurring revenue of $1-3 million without needing to spend more than $1-3 million to get there. That’s the sign of a strong product and efficient team. Another metric is that you should be on track to triple sales next year, as part of a five-year plan to get to $100 million (this is called “Triple, Triple, Double, Double, Double”). Another metric is the quick ratio – investors want to see you are adding at least $4 of new business for every $1 of business you lose from churn.

For a consumer business, there is a nice list of “wow” metrics published by Andrew Chen at A16Z:

1) cohort retention curves that flatten (stickiness)

2) actives/reg > 25% (validates TAM)

3) power user curve showing a smile — with a big concentration of engaged users (you grow out from this strong core)

3) viral factor >0.5 (enough to amplify other channels)

4) dau/mau > 50% (it’s part of a daily habit)

5) market-by-market (or logo-by-logo, if SaaS) comparison where denser/older networks have higher engagement over time (network effects)

6) D1/D7/D30 that exceeds 60/30/15 (daily frequency)

7) revenue or activity expansion on a *per user* basis over time — indicates deeper engagement / habit formation

8) >60% organic acquisition — CAC doesn’t even matter!

Andrew says nailing down even one of these would make him take notice.

When it comes to deeptech, the trickier your engineering effort will be, the more bets have to go right for you to win revenue, and the more cautious you should be about declaring to yourself and your Seed investors that your Series A hurdle metric will be revenue. For a biotech, the Series A hurdle might be achieving pharma interest in a data package; for a hard tech, demonstrating a working prototype with breakthrough performance could be enough if there is a clear market for the resulting product.

Andrew Lau the CEO of Jellyfish (which sells software to help middle market companies track and manage engineering projects) raised Seed from Pillar and Accel and then used his budget to co-develop his SaaS product with a dozen carefully selected accounts. He charged them each a low fee – enough to show they had real interest, but not amounting to much revenue. Since that was his plan all along, his investors did not expect revenue, and he did not have to waste any Seed cash on a salesforce. He then raised a strong Series A from Wing using the customer testimonials.

If you aren’t sure what hurdle metrics will be needed to raise your Series A, don’t fly blind. Figure that out right at the start, before you spend your Seed money, so you can navigate to a good result.

The best way to do that is to identify start-ups similar to you who have recently raised Series A. Call these CEOs to introduce yourself and ask what hurdles they hit. Most will be glad to help you along, as long as you are not a direct competitor.

Now update your plan and budget to make sure you are on track to hit your hurdle metrics using the cash you have available. If not, replan

Keep referring back to these hurdle metrics, so you can honestly assess if you are ready for Series A.

2: Constantly Review Your Fume Date

As the Seed period unfolds, start every month by looking at your budget and projected cash balances, and count how many months you have left before your fume date (the day you would have to shut down if you do not raise more cash).

This is so important. At Pillar, we urge CEOs to announce the cash balance and months of runway at the beginning of every Board update, call, or meeting.

Our rule of thumb is that you need 6 months to run the Series A process.

So every month, you should be projecting the date when the company will hit its Series A hurdle metric and comparing that to see if you will get there at least 6 months before the fume date.

If this is you, well done! Skip ahead to the next section. If not read below:

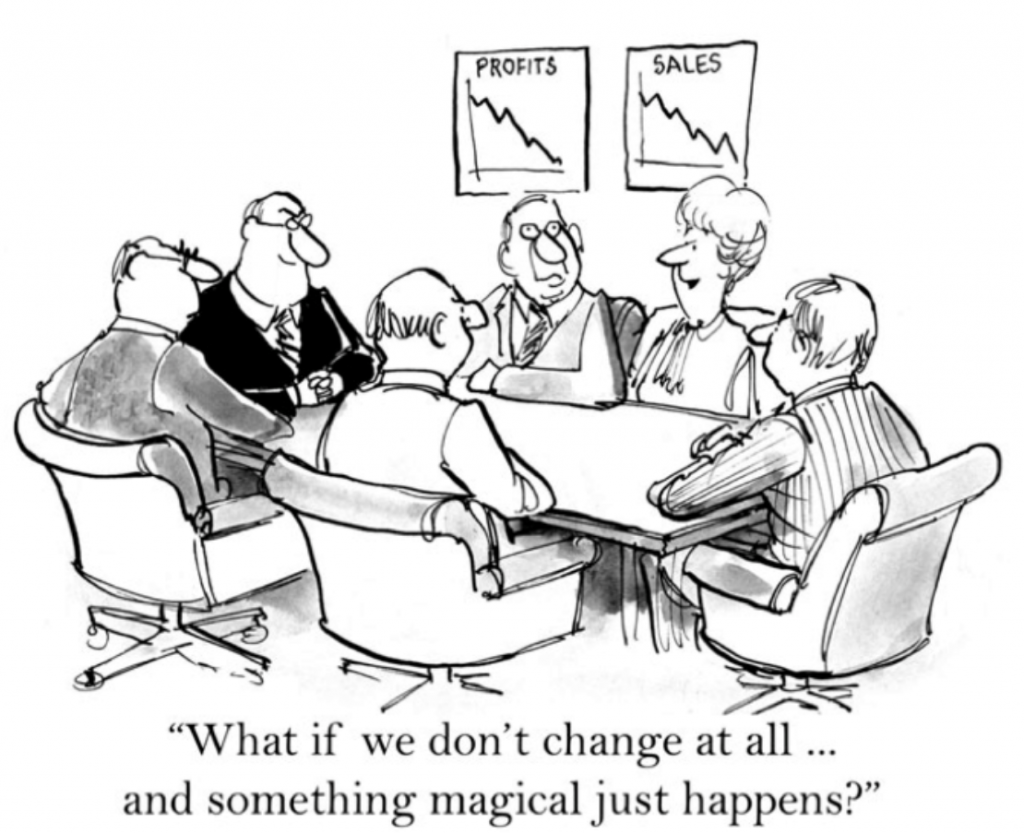

The day that you realize you aren’t going to hit your seed goals with the cash you have remaining is a sad day. It feels so painful that many CEOs trick themselves into believing they do have product-market fit. Then they try to raise Series A anyway. They waste their time and fail.

Don't put your head in the sand.

Take action while cash remains.

Tighten your product scope and narrow your market focus, so your team has a better chance of success. Slow your hiring, so you have more time for cycles of learning. Get outside advice and ideas. Improve your plan.

If you make adjustments early, you may still have a chance to achieve product-market fit without raising additional capital.

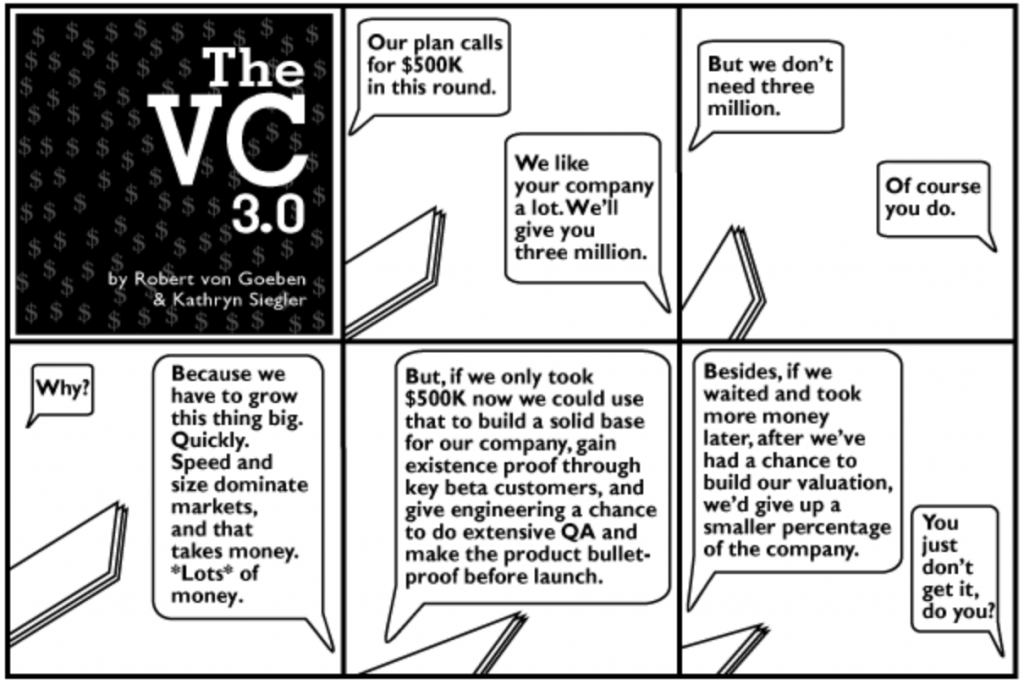

This creates a funny dynamic. The VCs who suspect you will need more cash may not say anything to you at all. They may be happy to invest more! They may hope cash starvation will make you get more creative. Or, they could be uncertain about your prospects and feel that the longer the seed extension is delayed, the more information they can learn.

Seed VCs face less time pressure than a CEO who wants to raise Series A, because raising money from inside investors can be fast – just 1-2 months for contracts to be signed. Prior to that, the natural seed VC instinct is to keep the wallet shut and eyes open and wait to see if the Series A effort succeeds.

That is why it is up to you to identify the need for a seed extension early. Waiting for cash to run out will come back to haunt you. If your runway drops below 6 months and you still do not have product-market fit, the company suddenly looks weak and desperate. The VCs who suspected this was coming and did not see you take corrective action lose faith in your leadership. They will encourage you to stay heads down on fixing the business and hope you turn it around. Then they will delay risking additional money until the last possible minute. That will be stressful on you and your team, and makes you vulnerable to bad terms or a shutdown.

Avoid drifting passively into that morass! Bite the bullet well before the fume date, ideally 9 months before, while everyone still feels optimistic.

Say “As you know we have learned more and created a new plan. While we all love the new plan, it shows we will not be ready for Series A before the fume date. Let’s raise an inside round now, so we can pursue the new plan and feel confident to reach Series A gracefully.”

If you raise a seed extension, you won’t be alone. More and more companies are raising extensions as they try to hit difficult Series A hurdles and gain attention from a short list of top Series A investors. Data from LP firm Cendana here suggests that the average time between Seed and Series A has gradually risen from 12 months to 18 months and that there has been a rise in seed extensions.

If you raise a seed extension, you won't be alone. More and more companies are raising extensions as they try to hit difficult Series A hurdles.

How much? The seed extension should be enough to fund your plan all the way to product-market fit, plus 6 months of runway to raise Series A.

Will the VCs agree? Most VCs reserve at least $1 for each $1 they invest at seed. They won’t want to spend all of their reserves too soon, but if you can get to product-market fit with a seed extension that is about half of your original seed amount, then you know they can afford to participate IF they believe in your updated plan.

Accept whatever

valuation the insiders need.

It's better to take moderate dilution now than to shutdown 9 months from now.

If your investors refuse to offer any seed extension that fully funds your new plan, then you are getting a negative market signal. Don’t ignore it. Immediately come up with a new plan that relies only on the cash you have.

3: Prep Your Team

[9 months of runway left]

When you see the company is on track for a successful Series A raise, start laying the foundation. This pre-work begins ideally 9 months before fume date.

The Series A raise will take a LOT of your time. That is why you ought to begin first by battening down the hatches and preparing for an absence – your own.

Imagine you must leave for a 3-month vacation. How would you organize the company to function without you?

Not sure? Here is a tip: delegate everything you do on a daily basis to someone else. Only keep your weekly and monthly meetings and check-ins.

Many founders have a hard time with delegation. Some believe “I do the most work of anyone and I do the best job of everyone”. If this is you, get over yourself, and get out of the daily work! You can’t make it very far as a leader if you do the work yourself. Reorganize or upgrade the team as necessary.

Free up at at least 50% of your time from now until the closing of the round. If there are projects you cannot support with the time you have left, cancel or defer them until after the round closes.

Many founders have a hard time with delegation. Free up at least 50% of your time from now until the closing of

the round.

Calendar cleared? Now you are geared up, and ready to go!

4: Meet Future Investors

[8 months]

During your seed stage, you may be contacted by investors seeking to meet you, especially if your company has received press coverage or if it is backed by well-known seed investors. You may also be invited to pitch events, or to industry panels where investors are in the audience. Sometimes you will meet VC partners and more often you will be canvassed by associates. How should you respond?

Our advice is to maintain a spreadsheet with the names of any interested investors who are chasing you. Don’t automatically respond to them all. Carefully examine each incoming call to decide if the investor could be a fit for your Series A (more on the factors to consider below). If so, take the call and see what you can learn about the firm and its investing priorities and style.

During your seed stage, you may

be contacted

by investors seeking to

meet you.

Here's how

to respond.

Dave Balter calls this stage “the Wind-Up” (to be followed later by the Pitch – read his insightful comments on fund-raising). He says this stage is “Just casual glad-handing, coffee meetings and character-setting. A good Wind-Up will inform who you have chemistry with. Nothing will happen without chemistry.”

Dave is a fund-raising master. He likes to stay in the Wind Up phase while polishing the way he explains the Vision and at the same time, step by step improving his management Team. At a certain point he senses that the VCs are starting to ask him to come pitch and he senses he has momentum. That’s when he goes into execution and pitch mode, with a goal of trying to get to a term sheet in just a few weeks. He will not go into pitch mode until AFTER he senses from these coffee meetings that he has momentum.

Follow two rules when you accept meetings with VCs who approach you too early:

1.

Be clear that you are NOT fundraising.

to prepare thoroughly, put your best foot forward, and then run

a tight process to generate multiple offers at the same

time. That can’t happen if

you start working closely

with one investor ahead

of the rest.

2.

Make it mostly a social meeting.

Should you reach out to schedule meetings with other VCs “for coffee” at this stage? Our general rule is NO. Wait until you have your pitch before you start calling anyone. Many VCs are super busy and inclined to make snap judgements – and if you knock on their doors now, you may not get a second chance later.

5: Develop Series A Budget

[8 months]

Another decision is how much cash to assume will be generated by future revenue to fund future expenses. Generally, you should not rely on profits from revenue to create free cash flow for your growing start-up during Series A. Growing companies generally do not generate free cash from sales – too much cash is consumed for costs of customer acquisition and working capital (inventory and receivables); and you will likely not immediately hit your cost or CAC goals right out of the gate. So, for the moment, plan on minimal free cash generated from sales despite growth. If you do better, you will be ahead of plan on cash and this will extend your runway.

If you don’t personally enjoy spreadsheet work, hire a part-time CFO to help you model out these scenarios, and circulate them to your Board for comment.

Once you know the amount you ideally want, let’s say $12 million, cut it down by 25% and reconstruct your baseline plan around raising 25% less, e.g. $9 million. Start by assuming the smaller raise because working with less cash is a good discipline that will force you to set priorities more carefully. If your funding efforts are going well, there will be excess demand to invest and you can walk the round size up later. If you are not doing well and cash is hard to find, you will be glad you set expectations a bit lower.

6: Check Your Valuation Goals

[7 months]

Series A companies – businesses with unicorn prospects, a promising product, but only roughly $1 million in sales, and raising $7-18 million – are currently being valued in the range of $20 to $40 million pre-money. Where does this come from?

A key law of nature in venture rounds is that each round will sell between 20-35% of the company.

In theory, the valuation ought to be based on some objective assessment of the risk-weighted discounted future value of your exit, and therefore valuation ought to vary based on the specifics of your company and market and you. In reality, valuation is about splitting the pie in a way that gives everyone enough skin in the game to stay committed.

For example, Series A investors have figured out over time that founders are usually willing to give up at least 20% in order to move to the next phase of building a business. So (if they are disciplined) they will never agree to buy less! However if they take more than 35% of the pie at this stage, the Series B investors will complain that the Series A investors were too greedy and they will force a restructuring. So (if they are wise) they will never agree to buy more!

The same principle holds for each successive round, which is why in general every round creates 20-35% dilution, regardless of the amount you raise.

Therefore if your funding need is $12M, for example, you can pretty confidently predict that if you can create 1 or 2 term sheets worth of demand, you will be seeing valuations of about $24M, and end up taking 33% dilution.

The specific split will come down to the amount of demand you attract and the ownership targets of the VC funds looking at your deal.

In general, every round creates

20 - 35% dilution, regardless of

the amount

you raise.

If you can’t generate enough interest, you will have to drop back to a smaller round, and that will also take 33% dilution. For example $7M on a pre-money valuation of $14 million. If you generate lots and lots of interest, inevitably you decide to expand the round, and once again you will also take 20-35% dilution. In an extreme example, $30M on a pre-money valuation of $70 million.

Save yourself some time – if you are not prepared to sell 25-33% of the company to raise cash, don’t go down the road of raising Series A from VCs.

7: Get Your Board on Board

[7 months]

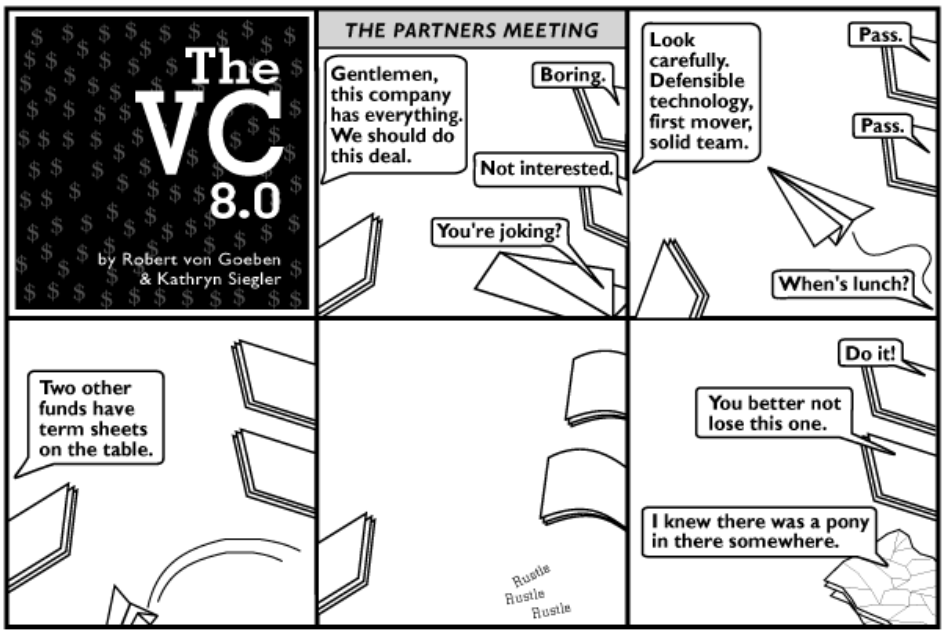

It is quite hard to raise Series A from new investors without a lot of love and support and endorsement from your existing Seed investors.

Additionally, in most cases you will need a Board approval and probably also a Seed investor majority approval vote before you can close a new investment.

Before you start working on a round, make sure you have obtained the approval and support of all Directors and key investors.

Sometimes this discussion will spark a pre-emptive offer. One of your bigger investors, or perhaps the entire Seed group of investors, will offer to invest on an inside round. “That’s a lot less distracting and easier for you,” they say. What to do?

This is a gut check moment. Will you truly achieve product-market fit at least 6 months before your fume date? If you feel doubt, then use this as an opportunity to close a seed extension and be grateful.

If you think you are a top Seed deal on track for Series A, then our typical advice when faced with a pre-emptive inside offer is to decline politely. Insist on running the process and obtaining an outside term sheet because it assures that both investors and you will discover the fair market price. This also helps you to broaden your base of investors and bring additional pockets to the table.

The typical Series A round recently is in the range of $7 to 18 million. That’s a big range. How much do you need?

Your plan for Series A should reflect a transition in company focus. Whereas the company’s goal during Seed is to achieve product-market fit; the company’s goal after you close Series A will shift to commercialization for the next 12-18 months. It is mostly about sales and operations, resulting in clear signs of revenue growth.

You will drive that company-wide transformation by hiring new department leaders. You probably already have a VP of Engineering who led the product development; now you will hire talented leaders to run marketing, sales or customer acquisition, customer success and operations, and perhaps finance.

It is pointless to raise capital unless you

know what to

do with it.

So, start developing

a plan and a budget for how you would spend

Series A funds.

Some founders find it helpful to set aside their current organizational chart. Starting from a blank sheet of paper, imagine your company two years from now, when the Series A money has been spent and you are closing Series B, and you are likely in the $3-10 million range. How is the company organized? What type of executives do you need and in which order? Answering this question tells you which VPs and Directors you need to hire in the next calendar year. P.S. and if you can hire 1 of them even before you finish closing Series A, that reduces risk and adds luster in the eyes of your prospective Series A investors.

Plan to hire proven department VPs who have already helped companies grow from $1 to $10 million, exactly what you hope to do over the next few years.

Although you might hire a few engineering heads, the purpose of Series A is generally NOT to add a second product. Leave that for Series B. When the CEO wants to spend all of the Series A money on engineering, that can be a “tell” that the company’s current R&D group is struggling, or that CEO is too technical/product focused and not thinking about the business as a whole.

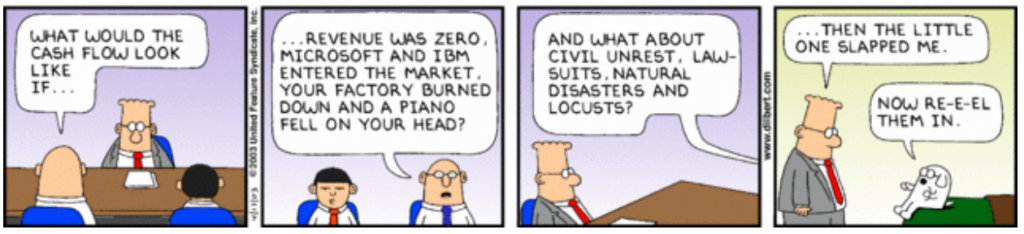

Many CEOs wonder how aggressive their sales projections should be. Any sales targets for the short run (before closing Series A) should be quite low, so that you can be certain to hit the goals and deliver good news while the Series A process unfolds. The sales plan for after Series A closes should begin with six months of cautiously rising numbers you feel 90% likely to hit, and beyond that, your sales projections for fundraising all the way out for the next 5 years should be based on the assumption that all goes 100% according to plan. What? Yes! Show investors what you hope happens. Investors are adept at imagining how the business can stumble and they will immediately apply a mental discount to your year 2-5 figures. No point in applying your own risk discount, on top of theirs.

Fundraising is not

a time to be bashful!

Paint an image of the business you will build if everything goes exactly as you intend.

Double-check that your vision of the thriving business will lead to a unicorn valuation e.g. sales over $100 million. If your opportunity is smaller that is fine, but you better skip the Series A VCs. They only want to see unicorn-scale ideas.

Showing the upside does not mean inventing fantasy numbers. You must be plausibly aggressive. It takes a lot of homework to develop a plan that is rational. You have to show investors how the numbers are achievable.

Create a detailed model underpinning each top-line number. For example: to hit the revenue figures, how many customers at what ASP, what sales cycle lead time and how many sales reps needed at what quotas (or how many leads or hits needed and how much advertising). What percent market penetration does that require? Exactly how many heads in each department month by month, and the salary for each position, and the number of heads you would need to hire. Develop a roadmap for product development and new feature release.

8: Add Luminaries

[7 months]

One cheap way to drive up your perceived value and chance of success is to recruit a few famous experts and well-known industry figures to help. They can become Scientific Advisory Board members, consultants, strategic advisers, Customer Advisory Board members, or even independent Board Directors.

Working with your Board, establish a small option budget and go recruit these luminaries. Not only will they give you practical advice and customer referrals, their stature will elevate your start-up. You gain credibility and value. The fact that you could recruit such busy people is a sign of your sales ability and competence.

9: Write Your Materials

[6 months]

Prepare 3 key documents ahead of time:

- Brief deck – 12-15 slides – you can forward this with an introduction and walk it during your first call or meeting. Do NOT put this in DocSend because investors hate DocSend – investors do a lot of behind-the-scenes discussing of companies with their internal team, fellow investors, and expert advisers and they need to be able to do that easily and privately. So you WANT them forwarding your deck for this purpose. Just expect it to circulate widely and think of this as free advertising; assume your competitors will see it.

- Longer deck with Appendix – 20-25 slides PLUS up to 50 slides – for use with an interested investor who schedules a second meeting or site visit.

- Dropbox / Data Room – a folder set up with all the materials that an investor would need to see to write a term sheet, including cap table and seed round documents. This is private information, so you only grant access to this after a VC partner has expressed serious interest. It is customary not to require a formal NDA when you are working with professional VCs. Do get a formal NDA if you are discussing a strategic corporate investment.

10: How to Draft a Killer Pitch Deck

[6 months]

All pitch decks for a venture-backable company need to show (1) you have identified a target customer with a painful need; (2) you can serve the need with a product or service that earns a profit; (3) the market is large enough to build a unicorn-scale company; and (4) as you grow you will develop a moat that protects the profits you earn. A VC must believe all four to consider an investment.

By Series A you are already shipping a product and have some small sales, so typically you do have evidence to support your claims 1 and 2. The goal for a powerful Series A deck is to awe investors with your answers to 3 and 4 so that they become convinced you are a unicorn in the making.

Seed was about whether you

can get in the game.

Series A is about showing you can win the game, and why this is a game well worth winning.

For Series A, the deck should have five elements: (1) a trend or attention grabber that explains why this market and major value is in transition right now; (2) the insight you reached during seed that led you to build an unexpectedly compelling hit product that the early customers love; (3) data that shows positive initial trends for your sales, operating, and profitability metrics; (4) the industry dynamics and the reason why fast growth will cause your company to achieve a permanent strategic advantage that assures years of profits; and (5) a specific plan for how the additional Series A investment will result in rapid growth.

Writing a terrific pitch deck is hard, just like writing a hit song is hard.

VCs make their money on hits, like platinum record deals. A Series A venture fund can only thrive if it manages to find and lead one of the top 10-20 venture deals in the USA each calendar year. Anything less is a failure in their eyes, so you need to be building a business of that caliber if you want to raise Series A venture capital. Help the VC to see how you are building an extraordinary company. Show how you will make an impact on the world, and how you will become one of the best deals in their portfolio. Don’t shoot for average.

Series A venture funds can only thrive if they lead one of the top 20 venture deals each year.

Don't shoot

for average.

We see highly successful Series A pitch decks start with a first slide or slide sequence that grabs attention and opens the mind to big possibilities. See a library of 15-20 different examples here.

The best first slides surprise the audience with an insight – an observation of a major transition happening in society (“the next generation wants to rent, not buy”) that leaves the audience nodding along, and signals there is a coming shake up in how people spend. This creates an opening for new entrants like yours to seize leadership. Andy Raskin has a nice post.

Consider how to frame your company’s industry. Is Tesla a battery company? A car company? An energy company? A software company? A lifestyle brand? A community? Pick the most valuable positioning for which you have a solid, credible claim.

Hit songs have a “hook” that listeners love, so think about yours. What is going to make your company particularly important and valuable In the future? Focus on business model, barriers to entry, network economics, competitive dynamics. How do you build outsized value? Why is this a profit machine? How do customers become hooked? What is the implication of your company’s success? Is it economies of manufacturing scale? Technical leadership? A unique channel? SEO content? Who will respond? Will this company create a major change in society? What new opportunities are created if you succeed with this first product?

In terms of what to cover, you can go back to the Pillar pitch deck template (here). Now insert that attention-grabber slide up front. Add detailed slides that show the specific proof of product-market fit as it applies to your business and as we described above. (If you don’t have the proof yet, stop! You’re not ready for Series A.) And add whatever slide(s) will really drive home your hook.

Now go back, polish, and refine it down to an intro deck that is 12-15 slides total.

When you are done, hire a graphic artist to give it polish and flow. The visual quality of a business presentation matters more than you might imagine. Having an editorial eye that organizes ideas and eliminates clutter is a way to demonstrate that you know how to prioritize. Keep it simple, clean, clear, attractive, lots of white space, readable font sizes. Deliver just one point well on each slide. If you don’t want to hire an artist, Dave Balter suggests “Get to know Unsplash and 500px and your slides will do the work for you.”

Expect to go through several different rewrites and a lot of conferring with your Board and advisers. You are writing the brochure to help you sell someone a piece of paper for $12 million. It’s got to be great! (The paper being a stock certificate).

11: Practice with Friends

[6 months]

After you draft a pitch deck, start working on your presentation.

There are only so many perfect VC investors who can lead your Series A. It takes weeks to get those meetings set up. Don’t waste your best chances. Get to know the pitch so well in advance, that you can crush every meeting.

Great CEOs practice the pitch at least 20 times before they start important investor meetings.

This can be alone, to your dog, for friends and current investors, or it can be with Tier III investors who are long-shots or slightly out of your target zone so you can “break some eggs” as you refine the message.

Once you have the pitch in your bones, you can go in ready to deliver a great talk without a lot of mental energy, which allows you the extra bandwidth you need to watch your audience as you talk. Be ready to go off script as needed, adjusting to the style and interests of the person listening to the pitch. You will be able to do this best if you know your material stone cold and don’t have to think about your talking points.

The 12/6/2019 podcast episode of Build by Maggie Crowley gives a vibrant, clear explanation of how to draft a strong business presentation.

A presentation method that works well here is an “accordion” style. Be able to explain each slide at three different levels, and then compress or expand as time allows.

The compressed version should be just one declarative sentence per slide. Let’s say you have a bar chart. Perhaps you can show the slide for a few seconds and simply say “Heavy Email Users Want More Speed” and the VC nods along. Flip.

Be able to explain each slide at three different levels.

Compress or expand as time allows.

Across all of your slides, memorize your key numbers. Interested VCs will ask lots of probing and what-if questions and you need to know your numbers to be able to answer on the fly. Great CEOs know by heart the sales targets and headcount targets for every month for the next 12 months and every year for the next several years, and they obsess about their business metrics like CAC, LTV, commission rate, ASP, days receivable, average salary for different positions, and so on. Such numbers are vital to building an actual company and so your modeling them in advance and internalizing the targets is a sign of operating competence and readiness; not knowing them is a sign you and the project are still green.

Across all of

your slides, memorize your key numbers.

Not knowing them is a sign you and the project are still green.

Make it easy on yourself and just use that sentence as the title for each slide. You can flip the entire deck at this level in less than 5 minutes. This title tactic is also endorsed by Eric Paley here. Imagine you fly out to San Francisco and endure the traffic and you get to a key meeting and the VC announces that he or she has a fire drill and can only spend 20 minutes with you today after all. Inside, you are mad and flustered! But you are not defeated. As you grapple with these emotions, you stay right on track by just explaining your bio (2-3 minutes) and then flipping your deck, reading the titles slide by slide. You are done by minute 10. Wow you look hyper-organized and used only half the time! After the VC realizes he or she is actually looking at a hot deal and a competent CEO, the VC can follow up.

If you make your titles like this, a key benefit is that anyone can read your deck and understand your message without you standing there to explain the slides. It is important that the deck stand on its own.

The medium-speed, normal version allows one minute of talking from you per slide: “We interviewed 150 heavy email users and asked them about 8 different reasons why they would consider changing software, and this bar chart shows the top reason each person selected as a percent of responses. As you can see, a staggering 40% of heavy email users are eager to try a new email client that would save them 15 minutes per day. So that’s where we focused our product development effort for the past year. I’m sure you would like to see the results! (flip to next slide to discuss beta user testimonials)” This is how you would present the slide if you have a one-hour appointment. First there is a comfortable 5-minute start, then twenty slides at one minute each allows for 20 minutes of you talking, and then plan for 20 minutes of friendly back-and-forth discussion with the VC during the pitch, and then 15 minutes of feedback and conversation and planning for next steps at the end.

The expanded, 3-5 minute version for each slide gives you room to add a colorful story or anecdote if the chance presents itself. You don’t have time to tell 20 stories for the 20 slides, but when you do see the audience is very interested in a topic, you can tell that story. Let’s say you hear a VC ask “How did you collect this survey data and what else did you learn?” Now you know the VC is interested in market research (!), so let’s dive in. “This data comes from the trade show where we asked people to rate their email use and focused on people who send 100 emails and up per day which qualified them as heavy users. Then we scheduled a follow-up visit to their place of work. We watched how they checked and answered their email, then asked them questions according to a structured guide. So many mentioned time pressure! (VC nods) Let me tell you about Lucy. Lucy works as a real estate agent, and when she gets an email from a prospective client, she has to respond within a few hours to have any chance to get the business. Her problem is that she is often squeezing in her email replies while she is parked between appointments. So, she needs a quick way to screen her mail and tag some to handle that evening, some for her assistant, and then she can easily see what’s left that needs immediate attention.” This story really impresses the VC both for its content and your diligence.

As you practice, bring a co-founder or teammate with you to help watch the audience and take notes. Write down every question you get. Then go back later, and polish your slides, re-order, and develop new materials so that the next audience will be less confused and more convinced.

12: Circle Up Your Insiders

[6 months]

With your pitch ready and practiced, it’s time to go to your insiders who know you first, and put the question – what is their appetite to participate in the Series A?

To give you any official answer, your Seed VC or angel group partners will likely need you to come back and re-pitch their partnership. Be careful NOT to do this until after your pitch is working well, because a bad impression really hurts your reputation, while a great pitch could spark your existing investor to invest more and also to work harder on making introductions for you.

After the pitch, ask each insider “Assuming we can generate enough demand to raise the Series A from credible investors and the valuation is in the ballpark, how much of the round would you want to take?” Be ready to tell them the size of their pro rata right. In most cases, their pro rata right gives them the guaranteed right to buy the same percentage of the next round as their fully-diluted ownership percentage. For example, if they own 14% of the company now, and you raise $10M, their pro rata would be $1.4 million. If they invested that, they would continue to own 14% after the Series A as well.

What you want to hear is that the insider is planning to take their full pro rata amount or even more. If they tell you “let’s wait to see who leads the round” that is less helpful. Ask them directly if you can count on them for at least a minimal level of participation, so you know what you can count on.

If insiders remain evasive, this is a bad signal. Go back and rethink whether you really have an attractive Series A proposition.

If insiders remain evasive when prompted about future rounds, this is a bad signal.

You need to get this question answered as tightly as you can before you start meeting with outside investors, because outside investors definitely will ask. No new investor wants to buy into a lemon; they want to know that your insiders are eager to invest as well. You would ideally like to be able to say, “We are raising $8 million, of which insiders will take $2 million.” That communicates a bullish note from insiders, while still leaving plenty of room for the lead.

13: Research Your List

[6 months]

If your company is ready for Series A, then the greatest factor that can reduce the effort required to run the process is to invest heavily in researching your targets before you start scheduling meetings.

Why?

The typical Series A partner will lead just 1 or 2 deals per year. Think about that… they review hundreds of companies and give out perhaps 3 lead term sheets per year, and win just 1 or 2 deals!

VCs have limited ammunition

and can only pull the trigger a few times a year.

Because of this need to select, VC partners are extremely fussy. It’s not just a question of whether your company will make money, but also a question of whether your deal will make them more money than the other hundreds of choices.

A common tactic of Series A partners to help identify the best of the best and to appeal to the CEOs they like is to specialize in a domain. They may focus purely on enterprise SaaS, vertical SaaS, consumer products, cloud infrastructure, deeptech, fintech, biotech, agtech, AI, virtual reality, robotics, blockchain, transportation and logistics, cleantech, sports, real estate, workforce and recruiting, eCommerce, marketplaces, business intelligence, food, gaming, health services, manufacturing, media, marketing, semiconductors, or something else.

That is why a random referral to a Series A venture fund will usually be pointless. The choice of partner matters a lot. And for all you know, the fund does not even have a partner who covers your area at all.

A common tactic used by Series A partners to help identify the best of the best

is to specialize

in a domain.

This is why the choice of partner matters a lot.

Surprisingly, an off-topic VC might still take a meeting with you. VCs want to cultivate referrals and they measure themselves on how many deals they see. So if a mutual acquaintance gives your company a warm enough intro, the VC may take a short meeting just to be responsive. But unless you match up with their interest, you are nearly certain to hear a polite no later, no matter how great your pitch. This drains your time, saps your energy, and depresses whoever gave you the introduction – yuck!

To avoid wasting your precious time and energy, invest 20-40 hours of research to create a list of targets. Narrow it down rigorously before you ask for introductions, and be cautious about accepting well-meaning but unfiltered introductions. Protect your own resilience in the future by screening every target carefully now.

Begin by asking your seed investors to each give you 2 - 3 names where they can provide strong introductions.

Then identify other start-up companies who raised Series A recently, and who are similar enough for some insights to carry over, but not directly competitive.

Next figure out who. Who were the VC partners (and you need to look at partners, not firms) that led the Series A round for each?

For example, if you sell pet food online, look for a VC partner who has already backed 1 or more eCommerce companies but not pet food.

This takes elbow grease! To get you started, there is a partial list of Series A VCs organized by specialty on Signal. You also can find records of Series A financings on Crunchbase, Pitchbook, Google, the SEC (most Series A deals are recorded with publication of a Form D), the business press such as TechCrunch, Xconomy, Forbes, VentureBeat.

Screen aggressively. There are also a lot of VC funds out there that focus on Seed, or on later-stage, or that do not have any cash left, or that have not actually started making investments because they are still raising capital. None of these are relevant to you. “VCs without money” will still take your meeting (!), because they want to show potential wealth capital source they have good, fresh deal flow. These people waste your time. Cross out anyone from a VC fund who has not actually led a Series A deal in the past 180 days.

Cross out anyone who works at a VC fund that is already backing one of your direct competitors.

Pay extra attention to any partner who has already backed a company in your city and will therefore already be coming through town.

For all the partners remaining on your short list, carefully review their Medium blogs, LinkedIn posts, and Twitter feeds and also cross out anyone who turns out to be a poor fit for your Series A. For example, you make hardware and they say in a podcast “we never invest in hardware.” Believe them and move on.

Next to each remaining partner on your list, use your research to write down the reason why you think they could add value or see a connection to your company. “Sue backed TripAdvisor, so may be interested in our site that collects user-generated content.” “Beth has a PhD in materials science and we are developing a new material.”

Now prioritize into three levels: a Tier I list of strong-fit prospects at the most famous firms, a Tier II list of other highly appealing prospects from reputable funds, and a Tier III list of partners who fit on paper but work at regional, less well-known, small, or family office funds. Note that these tiers are not about partner quality or fit with you, but about volume of deal flow and signaling the quality of your company to future investors. Your chances are lowest at the Tier I firms because they are mobbed at all times, however, if you can win a term sheet from one, then this is a strong positive signal to everyone else.

Screen each VC firm before you even ask for the meeting. What are they saying about their investment strategy on the website and on their social media? Who is in their portfolio? What was their most recent investment? And why is the background of the person you are asking to meet a good fit for your project?

Screen each VC firm before you even ask for a meeting.

Corporate VCs come with baggage that make them too complicated to be good lead Series A investors. Save them for Series B and beyond. A few corporate VC funds work quite independently and may chase you for Series A; if so take care to evaluate their strategic fit. If your company’s goals are loosely supportive of their BigCo goals that can work, but if you plan to disrupt their core business, or if you guess they will want to buy you, then stay away. Never sell a minority stake to anyone you consider a likely acquirer because their insider status will deter other bidders down the road.

Finally, put your list in a Google Sheet or Airtable document and share it with your Board for comment and refinement. Create columns and as with any pipeline, track your targets by entering the date you achieve each step: intro scheduled, first call, site visit, due diligence, received pass, received term sheet.

You will soon fill those columns!

14: Generate Buzz

[5 months]

If you have any major announcements saved up, use them now. This is the perfect timing for a newsworthy press release. Work especially hard to gain coverage in start-up media and local PR in San Francisco, NYC, and Boston where VCs cluster.

If your business happens to advertise, you may also focus your advertising in these cities for the next few months so that VCs are more likely to be exposed to your product or service.

Use good judgement. A gimmick press release that does not contain actual news looks worse than no news. The fact that you will be speaking at an upcoming conference is only slightly helpful. The best kind of press release is a performance breakthrough, new product announcement, big customer win, or a case study from a satisfied user.

15: Pre-Schedule Travel Blocks

[5 months]

It is vital to meet serious investors in person, and a good forcing function to be able to tell them “I will be in town this week.”

Pre-planning the travel also gives you a chance to set up customer and strategic meetings while you are in town. Nothing puts a spring in your step like a bullish customer visit just before you pitch a VC.

There is a seasonality to fund-raising. Most VCs are on vacation in August and December and Spring Break. VCs are swamped with deals and have less attention span in September, January, and May. Consider timing your outreach for October, February-April, or June if you have the flexibility.

Block off 3 days in Boston/New York City and 1 week in Silicon Valley on your calendar for about 6 weeks from when you start outreach, and again at 8-9 weeks, and again 11-12 weeks from start.

16: Begin Reaching Out

[5 months]

Begin with Tier II prospects. Select 10 of them and for each one, use LinkedIn and consult your Seed investors to figure out how you can get a warm referral.

Referrals are critical. VCs are swamped by mediocre pitches and eager to ignore founders who do not have sales skills. If you can’t figure out how to get a warm referral, they will safely assume you do not have what it takes to succeed.

Referrals are only valuable when made with actual credibility and enthusiasm.

The most valuable referral you can get is when one of the VC’s existing portfolio CEOs knows you well and can vouch for you and your business.

Otherwise ask anyone you both know well enough in common to vouch for character in both directions. Ideally bring the referrer through your deck first, so that the referrer can truthfully say “I think this is a great person with a great idea.” The VC will pay more attention.

Next most useful, would be asking your current Seed investor for a referral, ideally a Seed investor who is bullish and wants to take more than pro rata.

The least useful is a referral from anyone who hasn’t actually seen your pitch, or doesn’t actually know the investor well enough to have mutual trust.

Your referrer may well ask you “send me a blurb I can forward.” A common mistake is to then try to pack in tons of information that will take 10 minutes for the VC to read. That is a book, not a blurb, and likely will be ignored.

Send no more than one paragraph! All you need to do is intro the topic enough for the VC to see if the deal is in-scope and relevant to his or her interests. If so, you can be sure he or she wants to review your deal and will take the time to read the intro deck, which is your goal.

Just give the headlines: “Elon is an experienced deeptech CEO who already has several big exits. His next company Tesla is developing the world’s most beautiful, reliable, safe, and fuel-efficient electric vehicle. The team has strong pedigree and industrial scale-up experience. Although an automotive start-up sounds capital intensive, they have a clever asset-light model to get into production plus a creative direct-to-consumer sales approach. They are raising a $8M Series A and all of the Seed investors – including impressive seed investor X – want to participate. Have attached their intro deck below.”

That’s it – six sentences is all it takes and all you want.

Your referrer will then forward that to the VC along with your deck and check interest, and if the VC has interest, will introduce you to each other.

Some VC partners – a high percentage if you have done your homework well – will immediately reply “Sure please make an intro” and your referrer will do so. Any who reply “Sorry out of scope, we don’t do deals like that” is crossed off the list.

You may see some partners delegate the deck “Thanks I am forwarding this to our associate Paul who loves cars.” It is a great mistake to become arrogant and demand that you must speak with a partner! Do not try to dodge the associate – that will create ill will. Instead, take any meeting graciously and pitch your best.

You want the associate to become your ally and champion within the firm – someone who can help make sure you get onto the partner’s calendar and stay top of mind. Associates are plenty eager to find great deals to bring forward, so if you have any shot at all, they are certain to mention you to the partner, probably in a 3-minute exchange that sounds a lot like the blurb with added color. Partners also rely on associates to describe how you come across as a businessperson – do you feel likable, competent, and driven; or inarticulate, unprepared, or stubborn? A brief “forgettable” or “impressive” makes all the difference as to whether the partner will pursue. Finally, associates know the partners very well and if a partner seems disinterested, associates will know if another partner might fit better. Take these meetings seriously, and treat the associates with respect.

(NOTE: not all CEOs agree – those who do a lot of fundraising feel that associates are time-wasters. Sure, if you are a serial founder, you may have the reputation to let you skip associates and go straight to partners, but if that is not you, just do the work and take the extra meeting. It’s fine.)

Principals are between associates and partners. Some principals have the authority to lead a deal; some can follow but will not lead; some work closely with a particular partner as a force multiplier. The same can be said for Venture Partners. Again, place no importance on titles. Take any meeting offered to you seriously and treat everyone with respect regardless of title.

It sometimes happens that you are simultaneously introduced to two different people at the same firm. That’s OK but you should immediately alert both parties “P.S. just realized my network has passed this to both of you in parallel, so if this is of interest to Firm X, please let me know who is best to meet first.”

If you live out of town, schedule video calls on Zoom or another paid service for introductions, and tell them which weeks that you intend to be in town.

During your first call, seize the chance to qualify the prospect. Confirm whether the VC fund is actively leading series A rounds. Ask the person “What is the sweet spot investment for your firm?” and find out what kind of investing they typically do. Ask “what are the last three deals you did?” and see if they sound anything like your deal. If you discover they do NOT normally lead deals or invest in your area, then put off further meetings until after you find a more suitable lead.

17: Pitch Meeting Basics

[4 months]

Arrive 10 minutes early, not more. After you get to the conference room, avoid the temptation to stare out the window. Immediately plug into the projector and confirm that your slides / WiFi / demo are working.

VCs appear relaxed and offer you coffee, but don’t show up to a pitch meeting planning to have a casual chat. Your VC is a professional and your time with them is limited. Remind them what your company does right at the start, because they take so many meetings. Allow five minutes of casual discussion to warm up, then introduce your bio and how you came to the project because they need to get a sense for who you are and to imagine whether they would like to back you as a person before they can concentrate on the details about the company. Then adjust your pitch pace to use up about half the remaining time, which leaves the other half open for Q&A along the way or at the end.

Always put your slide deck on screen, because some human beings need to hear information and other human beings need to see information, and you don’t know in advance which types will be in the room. Speech plus visuals delivers more information per second than speech alone, so it is most effective to broadcast on all channels simultaneously. Bring a small bag of connectors as necessary to be able to immediately adapt to the room.

Let’s also hear how Dave Balter suggests taking these pitch meetings:

“Pitch live when you can. Pitching via video works, too (zoom finally made this work well enough). Don’t pitch on a phone call. Always pitch with a deck. Pitch in an office, not a coffee shop. Pitch without Randos walking behind you all the time (no one cares about your shared office space).”

You want to come across self-confident, but not self-centered. Tod Loofbourrow adds further advice on style: “Avoid hype and pressure tactics like, ‘you’re gonna lose the deal’ because these sound arrogant and will be red flags to investors. Remember, both sides are trying to build trust. Trust is built over time. VCs have a real need to assess each CEO. They wonder: Are you coachable? Do you put the company’s success ahead of your own ego? First-time CEOs think they need to be the smartest person in the room and have all the answers. Experienced CEOs would rather be smart, collaborative, and humble; a good listener who can take feedback well and does use it to improve; and secure enough to bring in great talent.”

18: Handling Tough Questions

[4 months]

Here are a few questions you will get often, and how best to answer:

Q: What is your vision for the business?

Bad Answer: I want to flip it for a quick profit next year.

Good Answer: We will work tirelessly until we put a Coke within arms reach of every person in the world.

Q: After the round closes, who are your first three hires?

Bad Answer: a secretary, a customer support rep, and my brother who is a really good engineer

Good Answer: a world-class VP Marketing and 2 sales reps with golden Rolodexes, followed by a VP of Operations, and then a few months after that a VP Finance to upgrade our part-time CFO. (you have carefully thought this through in advance! you are greedy to hire the best people in the world!)

Q: What keeps you up at night / what is your greatest risk?

Bad Answer: nothing / the greatest risk is raising enough capital from investors

Good Answer: we have discussed this a lot. Our top three risks assuming we do get the capital are 1, 2, and 3. That is why during the seed we will do ____ to resolve 1; and ____ to scout out whether 2 will turn out to be a problem. We will then turn to focus on 3.

Q: How much are you trying to raise?

Bad Answer: we want to raise $20 million (you need $10M; hope VC offers half)

Good Answer: we need to raise $8 million to get to milestone X. If the syndicate supports then we would raise $10 million and get to milestone Y.

-> Approach your target size from below so you are sure to exceed expectations

Also, take a moment to learn the word “syndicate” – it refers to the investors as a group. This term is used frequently in finance.

Q: How do you want to see the round come together?

Bad Answer: two new VCs plus the insiders (bad answer because you don’t know if this investor is willing to work with a co-lead, you don’t know if there will be another interested VC to join, also you have just made life more complicated for everyone because there will need to be more heads around the table)

Good Answer: we want to pick the right lead partner and then work together to figure out the best and most compatible syndicate.

Q: Are your insiders participating?

Bad Answer: we haven’t asked / they are still deciding / it depends

Good Answer: yes they will take about $2 million assuming typical valuations and a credible lead

Q: What are your valuation expectations?

Bad Answer: we want $X valuation (any firm number will make you look bad if it appears too low, yet make the VC feel bad or give up if it appears too high – so you are very likely to cause the VC to cringe, no matter what you say!)

Good Answer: We will let the market tell us what terms are reasonable. As long as the valuation is at market, we plan to pick the investor who can add the most value and who feels the most aligned with our team and vision.

Q: When do you need a decision?

Bad Answer: next week (no way can the VC move that fast)

Good Answer: we are just starting to reach out so we would hope to see indications of interest or receive a term sheet in the next 4 weeks or so. (that leaves the VC enough time but not extra time)

Q: How long have you been raising?

Bad Answer: you are the 50th VC and we’re really getting tired

Good Answer: we have been reaching out for a few weeks to test the pitch with friends and now just starting in earnest

Q: Who else is in the mix to lead?

Bad Answer: “no one else”, or you actually name “Firm X”. That is bad if Firm X is a better fit/more famous than the VC you are talking with, because then the VC knows he or she will likely not win the deal and gives up; bad if Firm X is a poor fit/less famous than the VC you are talking with because you seem to be fishing in the wrong waters; bad if Firm X isn’t actually as committed as you think because if two VCs later compare notes you will appear to have exaggerated; bad if Firm X is their friend and they don’t want to antagonize them by competing for the deal; bad if Firm X is their enemy because they don’t want to have to syndicate with them; and bad when your interested VC asks about Firm X next week and you have to admit they passed – in short, in many, many ways naming a specific firm can backfire, so just don’t discuss your pipeline until after a term sheet is signed.

Good Answer: we have been running a robust process and we see several firms as potential leads, and your firm is of high interest to us. We are seeing a good reception and feel confident of raising the capital. We are not prepared to put you in touch with any specific parties at this time, but happy to do so and to work collaboratively to build out the syndicate if you become the committed lead.

Q: Why our firm?

Bad Answer: we found it on Google Maps near another firm and wanted to fill an open block of time

Good Answer: we are friends with X, one of your portfolio CEOs, and s/he speaks highly of your firm and made the introduction. We asked to see YOU (the specific partner) in particular because of your deep relevant experience in ____ and because when we read your Medium posts on ___ they made a lot of sense.

Q: (lots of substantive questions – what is your CAC, who are the competitors, etc.)

Bad Answer: uhh, we don’t know / a factually wrong answer / bullshit or evasion

OK answer: we will find out and get back to you (and you do get back before next Monday)

Good Answer: we already have a detailed analysis of that in the Appendix, see slides 17-21.

NOTE: as you take pre-meetings with friends or lower-priority investors, listen for questions. Every time you hear a new tough question, write a slide as an answer, and add it to your growing Appendix, so you are ready for it again in future. This will also help VCs who get into the process late to catch up, because all the questions that others took weeks to ask are already laid out in front of them.

Q: (a series of probing questions)

Some investors deliberately ask probing questions as a technique to test the CEO’s business acumen. (I got a lot of that at E Ink, perhaps more than most because I looked young.) It’s a kind of stress interview method of diligence. Great CEOs know their numbers cold and are paying attention to critical details.

To pass the test, just calmly make sure you understand the question, then answer that exact question factually and *without* spin. This builds trust and confidence.

The investor may consciously choose to continue probing more and more until finally, you do not know the answer. They want to see how you handle that.

Avoid the temptation to make up a story or deflect the question. Just candidly admit whatever you don’t know. Offer to get the information, and then do so, ideally within a day. Your humility and prompt follow-through will build further trust and confidence.

If you don't know the answer to a question, candidly admit that you don't know.

Offer to get the information, and then follow up within a day.

19: Taking Stock After First 6-10 Meetings

[4 months]

Now the rubber has hit the road! You warmly outreached to 10 prospects, probably got 6 meetings, so what are you hearing?

In the ideal case, the associates and principals are quickly moving you to partners, and the partners are meeting you within one week, then following up with a call or email also within one week. You are a hot deal.

In the normal case, most responses will be delayed replies or outright ghosting. All founders hate this waiting game. As days go by, you wonder “why aren’t they interested in my deal? And why not at least give me the courtesy of a quick no?”

There is no need to wait or to guess! If there is ANY chance the VC wants to lead your deal, he or she will worry about competition from other VCs and will contact you within one week. In fact because most VC firms meet to discuss their open deals every Monday, you will usually hear back by the next Tuesday if your meeting was a winner. They will call you to schedule the next meeting, and often ask you for additional materials.

The old adage is “Good news travels fast, bad news takes it time.” If you do not hear back by the following Tuesday, then just assume a No is coming. So don’t wait. By Wednesday of the next week, go to whoever gave you the referral, and beg him or her to call the VC and ask for impressions. This is going to make you feel vulnerable, but you MUST get this vital feedback. If the referrer does not know the person you met well enough to ask this, then ping the VC yourself, and say “can I call you for 3 minutes at end of day to check in?” and then ask him or her directly for feedback.

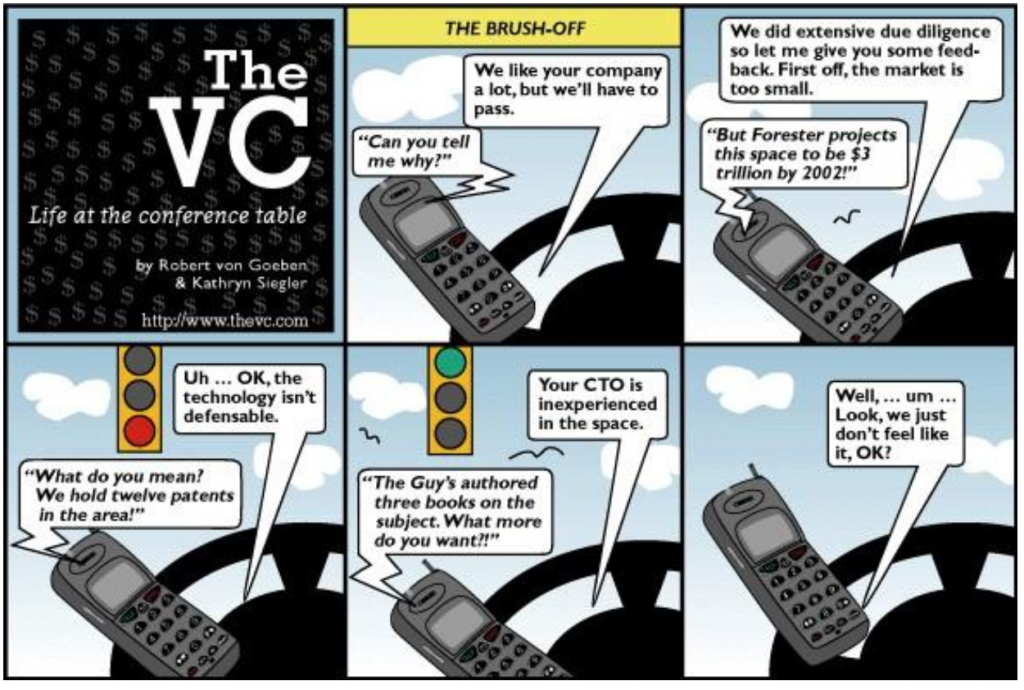

You will likely hear a lot of random feedback, sometimes opposite feedback. That’s OK. Investing is subjective and there will be many different reactions. Don’t change until you hear the same message repeated 2 or 3 times, but then take it to heart and do adapt your plan or pitch.

Keep iterating until you get at least some positive interest from Tier II. Now, immediately start calling Tier I as well.

What you should NOT do if the Tier II outreaches all fail is keep grinding ahead anyway and start calling Tier I. You take huge risks by staying the course and piling up rejections from famous firms. Your team can see the fundraising is failing. Your investors can see the fundraising is failing. You lose touch with your employees and your customers for months on end. You start to burn out from the stress. Your company earns a reputation as a shopped deal nobody liked, which is a stink that could take a while to wear off. The worst is that your Board loses faith that you can raise capital. Of the skills needed to be a start-up CEO, the ability to raise capital is the one of the most important, so this really harms your career.

After the first 6 or so partner meetings if you feel the wind missing from your sails, and the feedback does not point to anything you can fix easily, then accept reality and immediately halt fundraising. When you are in a hole… stop digging.

No other option? Cut your burn, so you can add more runway, and start over. Change your pitch, change your plan, and try again perhaps aiming at a different type of investor and raising a smaller round.

If it doesn’t work again, you must give up on Series A. Either close an inside round, or consult with your Board on how to sell the company now for whatever you can, before you have to raise more capital.

20: Managing Team Expectations

[4 months]

As VCs conduct diligence, your team will pay attention, help with diligence, and maybe even meet the partner. When the VC later passes, that can hurt morale.

Get ahead of this by managing expectations of your team in advance. Explain that they should expect to see 5-10 tire-kickers come through, before a term sheet is forthcoming. Warn them that VCs typically wait until just before the company runs out of cash before they will send in a term sheet. Help your team to have strong stomachs so that they do not get rattled by the ups and downs.

Although it can be difficult, try not to let the fundraising process dominate the hallway conversation – keep people focused on products and customers.

Employees are in a tough spot here – just as vulnerable as you and far less able to affect the outcome. They will be anxious and you should project a reassuring confidence. You cannot be 100% certain that the fundraise will work, so never promise that. What you can promise is that e.g. “if we do not have a term sheet by 90 days of cash left, we will ask the insiders for a bridge round instead”, and if you honestly believe the Board will be supportive, you can say “and I believe they will be supportive”.

21: Diligence Process

[4 months]

After your initial outreach shows some traction, you will continue outreach. If you rigorously narrowed your list as suggested above, then might reach out to 30 partners, take 20 first calls, and hope 10 firms show enough interest to engage, 5 firms really dig in, and 1-2 term sheets. That would be a strong raise.

It feels really bad to have a VC befriend you, visit your office, maybe even talk to a key customer or two, and then pass. You have to steel your nerves for it.

Sometimes they give a reason that makes sense, and you can think of a solution or prepare an exhibit and be ready next time. Sometimes they just pass without saying a reason and you worry that it came down to your personality. Hey, you might be right 🙂 but that’s why you made a long list of investors. Just keep meeting different types of people until you find someone who connects with you.

Often it has nothing to do with you or your company – they had another deal become urgent or go south and decided that they do not have enough bandwidth to think about your company any more.

Rejection is tough, but

you must

continue on.

Keep meeting different types of people

until you

find a

good fit.

Screening partners carefully during the research stage is a key way to protect your resilience. If you didn’t screen as rigorously, then you might need to contact 60 partners to get the same 10 firms to take an interest, which takes twice the effort and gets almost triple the rejections! That will weigh on any founder.

Engaged VCs will show it because they send you questions, come out to visit your office and look at your data room (10% likely to fund), then conduct a bunch of backdoor reference checking on you and the opportunity, perhaps invest further energy to speak with some of your customers and partners or arrange some new customer or strategic partner or advisor visits with you (25% likely to fund), and then invite you to come in and pitch their entire partnership (50% likely to fund).

Your goal is not only to get one term sheet, but ideally to receive two or more term sheets in the same week. This takes skillful juggling! Keep track of your investor pipeline using the probabilities above and keep adding prospects to the top of funnel, working your way from Tier II and then up to I or down to III if necessary, and keep at least 6 funds going at all times adding new prospects as needed so you always have options, until you actually sign the term sheet.

The wait for a VC to become convinced enough to give you a term sheet can feel agonizing. Take this as a test of your own maturity and integrity. Never make up facts to pressure a VC to get you a term sheet sooner. Never pretend you have a competing offer; never claim a firm remains interested who has passed. Lying will be found out and will destroy your reputation. If you have a good company then with enough work it will get funded, and if you do not, it will not, and no verbal positioning will make the difference, so don’t take a shortcut at the price of your own integrity.

If a VC asks about other firms submitting term sheets, never reveal the names. Speak generally.

If you tell them who is else is bidding, either they get nervous and think they will lose to a bigger fund and walk away, or they may think the other firm is bad quality and you look a little less spectacular, or possibly they are good friends with the other firm and they may start sharing impressions about you at the bar. Avoid names and if they want the deal then their active imagination will automatically fill in the firm that they are most worried about.

If all goes well, you will receive a term sheet from at least two VC firms and you can negotiate a fair deal from a position of strength. One term sheet is all you need in the end though, if it is reasonable and you like the partner.

22: Your Diligence on the VCs

[3 months]

If you are fortunate enough to see one or more VCs engaging in diligence and you sense that you may get an offer, it is time to do some diligence of your own.

The best way to think about selecting a VC is to mentally reframe Series A as primarily a recruiting activity. You essentially hire the VC today by paying them a cut of the profits your company hopes to earn in the future. Imagine you get to add one extra executive for your company who will not draw on payroll. Which of the VCs you are meeting would you most want to hire?

Unlike an employee, there's no way for you to fire your VC.

You better be sure there

is a cultural fit.

Tod Loofbourrow, serial founder and CEO of ViralGains, says the #1 priority of your Series A fundraise is to select the right person to be on your Board of Directors. It could be a partner or a principal, depending on whether you need gravitas or someone who will roll up sleeves and work alongside you. Either way, the ideal VC has produced star investments for their partnership in the past, which will give him or her the pull to persuade the rest of the firm to keep backing you if times get tough. Tod says “Stop worrying about valuation. In your first few rounds, don’t take the highest valuation. Take the best relationship.”

The best tool here is a backdoor reference check. Figure out who in your network knows a CEO who has previously taken money from this VC partner and call them up directly. Ask them how it has gone? Where did the VC add value? Where did the VC make the CEO’s life tougher? What is the VC’s style at Board Meetings? Do they miss, call in, or show up in person? What has the CEO learned about working with that VC successfully? What are the quirks and hot buttons? Is this person the very first VC they will call for their next company? Also, ask if the CEO has interacted with other people at that VC’s firm? How is that firm doing overall? What sorts of events or support have they offered and is it valuable?

Your best tool for diligence on a potential VC

is a backdoor reference check.

Ask everything

so there are

no surprises.

The ideal person to reach is a CEO who was backed by the VC and whose company failed. How does the VC behave when the results are disappointing? Were they become more active or did they check out? Were they helpful or distracting? Did the VC maintain composure and class as it all fell apart?

You want to start this work when a deal seems likely but still a few days ahead of receiving a term sheet, because once the term sheet arrives, you might need to make a decision quickly.

23: Picking a Term Sheet

[3 months]

After sending over a term sheet, the VC will likely want you to commit right away. Issuing term sheets is a nerve-wracking moment for a VC because it only happens a few times per year, and each time the whole firm is watching to see if that partner can convince you to sign. No VC wants to disappoint his or her partners, or get outcompeted by a rival firm.

So they will pressure you persistently to sign and that is pretty normal. On the other hand, a VC who jams you with a “take-it-or-leave it today” approach, or who refuses to talk things over, is not a VC who is confident of offering you the best deal. So be wary of high pressure tactics.

In terms of deadlines, unless it is the perfect deal, or there is some other good reason for urgency, insist on they allow you at least three business days to consider a signed term sheet.

If you have not done your diligence yet, perhaps because the process moved faster than you expected, now is the time to ask the VCs to provide references. Pick 2 or 3 of their portfolio companies at random and ask to speak to those CEOs specifically, which will ensure you get a sampling of good and bad rather than just the good. Make these calls before you sign anything.

Most term sheets are 3-7 pages long and full of legalese. So when you get a term sheet, immediately send it to your Board of Directors and your attorney and ask for comments and a markup. The attorney will compile a list of small or large legal issues. Your Board may suggest a counterproposal on pricing. You can send all that back to the VC, which will buy you another day or two to see if they will offer a better version.

What you do with that time depends on how much you like the deal

on the table.

What else you do with that time depends on how much you like the deal on the table. If you would be willing to sign the deal but actually prefer a different investor who is near the finish line, then call that investor up and say “we just got a reasonable term sheet from a reputable firm, and now we would like to see a term sheet from you before we decide. Can you get to a decision in the next 2 days?” Most will say no, but if that partner says yes, then you can come back to the first firm, thank them for sending a term sheet, but then say that another firm is also deep in the process and you have decided to give them 48 hours to put an offer on the table or walk away. The first VC may not like this, but has to respect that you are not going to pull the rug out from under an investor who has been in deep diligence, and 48 hours is generally a reasonable time to wait.

If the term sheet is something you can not accept because the terms are complex and filled with hidden gotchas, and your attorney looks like she wants to jump off a bridge, then stop and rethink. It could be that the VC is diabolical and you should run away. It happens. But it may also be the case that the VC thinks you are the problem because you are demanding an unreasonable valuation, or because your cap table is complicated by past financings, so he or she has to create a tortured offer. Go back and test this by saying “This term sheet has undesirable non-standard features. What valuation would you offer if we wanted to work with a generic, simple, clean structure?”

If the term sheet is OK but you do not really like the partner who gave it to you, then you are really in a tough spot because it is so risky to let go of a bird in hand. Call up everyone you like better in your pipeline and say “we have at least one firm indicating strong interest, can you give me a sense of your process and time needed to reach a decision?” Then you can at least make an informed decision as to whether to keep working your pipeline, or to accept, or to abandon Series A and ask insiders for a seed extension instead.

Please take this lesson to heart:

Your goal as CEO is not to

achieve the highest valuation for

this one round.

Your goal is to find a VC who is willing to invest enough money for your plan, on fair terms, and who is someone you will want to work with for many years to come.

24: Smushing VCs Together?

[3 months